Cartridges For Sale

Pinfire Cartridges & Boxes

Guns for Sale

Pinfire Guns from Around the World

Articles about Guns & Cartridges

Pinfire, Pauly, Perrin and more

In 1830, at a time when improvements in shotgun ammunition usually involved wire, paper, or increasingly clever mechanical contrivances, J. Jenour proposed something far simpler. He suggested baking it.

In an article published in Mechanics’ Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette (No. 367, August 21, 1830), Jenour described what he called “brittle charges,” a method of forming shotgun shot into rigid, bore-sized cylinders using nothing more exotic than flour, water, and gentle heat. The idea sounds absurd until one reads his reasoning, which is methodical, safety-minded, and quietly radical.

In the early 19th century, the world of firearms was on the cusp of transformation. Muzzle-loading flintlock weapons had dominated battlefields for centuries, but their limitations in rate of fire and reliability were becoming increasingly apparent. Amid this backdrop of military necessity and technological possibility, French inventor Joseph Alexandre Robert emerged as a visionary innovator who would help redefine firearms design.

Born in France at the turn of the 19th century, little is known about Robert’s early life. However, his passion for mechanical innovation and firearms technology led him to establish a workshop at 17 Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre in Paris during the 1830s. From this modest location, Robert quietly began a revolution in firearm engineering, introducing concepts that would profoundly influence the evolution of weaponry.

This article delves into Robert’s groundbreaking innovations, exploring how his radical breech-loading system, self-contained cartridges, and automatic internal cocking mechanism represented significant advancements over existing technologies. It also examines the impact of his work on military and civilian firearms, his rivalry with contemporaries like Casimir Lefaucheux, and his enduring legacy in the field of firearms development.

Nineteenth‑century hunters wrestled with two maddening behaviors from smoothbore shotguns: at one extreme, tightly packed pellets that flew out “like a ball” (the coup de balle), and at the other, errant flyers that blew patterns wide open. Period writers traced both to how the wad pressed or failed to press the shot during ignition: over‑compression could keep the column clumped for several yards after the muzzle, while under‑compression let pellets collide, deform, and veer off‑axis.

Pierre‑François Davoust, an armurier from Alençon, set out to cure both problems at once.

This unique breechloader began life as a Harpers Ferry Model 1842 percussion musket, a .69 caliber smoothbore muzzle-loader manufactured in 1855. Wohlgemuth completely overhauled the musket into a break-action breech-loading firearm. He fitted a hinged breech mechanism into the original stock and barrel, allowing the barrel to tip downward for loading, much like a shotgun. To secure the breech when closed, the original trigger guard was reversed and a cam-locking lever was added under the action. He also modified the nose of the percussion hammer to be better suited to strike the pins of the pinfire cartridges, and trimmed the wooden fore-end to accommodate the new hinge. Finally, an M1861 Springfield rifle-musket rear sight was installed on the barrel, giving the converted gun proper sighting for rifled fire. Each of these alterations was performed by Wohlgemuth himself, transforming the old muzzle-loader into a modern breech-loader while retaining its hefty .69″ bore, which closely matches the dimensions of a 12-gauge shotgun.

I’ve always been fascinated by historical documents. The thrill of holding an old manuscript, patent, or handwritten letter and uncovering the story it carries is like traveling through time. Over the years, I became an avid collector of these artifacts, from 19th-century French patents to century-old family letters, driven by a passion to research and preserve them for the future. Each document in my collection felt like a critical piece of history that I was responsible for safeguarding and understanding. However, as my archive grew, so did a realization: preserving and understanding these documents are two very different challenges.

The first challenge I faced was simply reading and translating the content of these historical papers. Many were handwritten in old-fashioned cursive or in foreign languages (like French, or German), making them hard to decipher. Before the age of AI, the process of transcription and translation was tedious and slow. For years, I spent a significant amount of money hiring native speakers to translate my old French patents and letters. These documents were often so technical and nuanced that only specialized translators with historical expertise could do them justice. Even with the best professionals, the turnaround was slow, expensive, and sometimes inaccurate due to the archaic terminology and challenging handwriting. It wasn’t just me. Any researcher working with primary sources knows the pain. Scholars might spend weeks painstakingly transcribing a single letter or journal entry by hand, time that could have been spent analyzing the content. And if the document was in a language you didn’t know, you either had to find a translator or risk missing out on valuable information.

My own workflow for dealing with these papers was clunky at best. I would scan or photograph the pages, then try a patchwork of tools and services: maybe an OCR program (which often choked on elaborate 1800s handwriting), followed by Google Translate for printed text, or sending images via email to a translator for the really tough scripts. Often, I ended up with pieces of the puzzle in different places – a text file here, a translation there – which I’d then have to compile and proofread. It could take an entire afternoon to get through a single page of a letter, and a full patent dossier could occupy me for days or weeks. All this drudgery was the price to pay for pursuing the hobby I loved.

Throughout the 1850s, a steadfast devotion to muzzleloading guns defined the British shooting world. Many sportsmen took pride in ramrods, paper wads, and the careful loading rituals they had practiced for generations, viewing the breechloader as a fleeting Continental curiosity. Lefaucheux’s pinfire system was especially scorned, with skeptics deriding it as “the French crutch gun.” Although some recognized the advantages of quicker reloading and the avoidance of stray powder spills, the idea of turning British sporting traditions upside down for a new invention provoked as much suspicion as enthusiasm.

Even so, a few forward-thinking gunmakers in Britain were quietly adopting breechloaders, banking on improved reliability and the promise of faster shooting. The real question became whether homegrown British ammunition could match or surpass the performance of the established French pinfire cartridges, which were already circulating among sportsmen who had traveled abroad. It was in this swirl of debate and apprehension that Eley Brothers stepped forward with their own venture into breechloading cartridges.

In the gunsmoke-filled world of 1860s Paris, as firearms technology was experiencing a revolution with the widespread adoption of breechloading weapons and self-contained cartridges, a determined inventor named Eugène Pertuiset was about to make his mark on history. The French capital was then the epicenter of firearms innovation – where revolutionary designs like the Lefaucheux pinfire system and the new Chassepot military rifle were transforming the possibilities of what guns could achieve. It was in this atmosphere of rapid technological change that Pertuiset would develop one of the most innovative – and controversial – ammunition advances of the 19th century.

John Krider was a name well-known among 19th-century American sportsmen, particularly in Philadelphia, where his gun shop became a staple of the local sporting community. Situated at the northeast corner of Second and Walnut Streets, Krider’s shop wasn’t just a place to purchase firearms; it was a hub of innovation and craftsmanship, where the latest advancements in gunmaking were adapted and perfected for the American market. Among the many firearms that passed through Krider’s hands, a particularly notable piece is a 12-gauge pinfire shotgun that exemplifies his blend of European influences and American ingenuity.

In the late 1800s, a legal battle erupted between two ammunition giants, the Union Metallic Cartridge Company and the United States Cartridge Company, over the technology used to manufacture cartridge shells. The case, which wound its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, offers a revealing glimpse into the early American patent system and the fierce competition in the rapidly industrializing arms industry.

At the heart of the dispute was a patent granted to Ethan Allen in 1860 (reissued in 1865) for a machine that could form the hollow rim of a cartridge shell in a single stroke, a significant improvement over prior methods that required multiple spinning operations. The Union Metallic Cartridge Company, having acquired rights to Allen’s patent, sued the United States Cartridge Company for infringement.

These cartridges, with their distinctive recessed rims, were the key product Allen’s machine was designed to produce efficiently. Forming this critical feature in one step was a major breakthrough.

In the tapestry of American firearms history, few threads are as colorful and as intertwined with the fabric of innovation as the story of Charles Edward Sneider and his journey with the pinfire system. This article ventures into the heart of 19th-century America, a time of rapid technological advancement and societal change, to explore the pivotal role played by Sneider, a Baltimore-based gun maker of remarkable skill and vision. Through the lens of Sneider’s life and legacy, we delve into the symbiotic relationship between the burgeoning United States and the innovative pinfire system, uncovering the profound impact of his work on the course of firearms development.

In 1837, the U.S. military tested several innovative new firearm designs in a series of trials at West Point and Fort Monroe. These included early breech-loading rifles designed to improve on the standard muzzle-loading muskets and rifles used by the Army at the time. The tests provide an intriguing look at the state of firearms technology in the 1830s as inventors sought to harness new percussion cap and self-contained cartridge systems.

One of the most advanced rifles assessed was a 1831 French design by Joseph Alexandre Robert, presented by Baron Charles Hackett. Robert’s rifle used a rear-pivoting breechblock to allow a paper cartridge with percussion tube primer to be loaded from the rear. This breech-loading system gave it a major advantage in rate of fire over muzzle-loaders. In testing, Robert’s rifle achieved around 5 shots per minute, similar to the rate for Hall’s breech-loader and far faster than the 3 shots per minute of the standard U.S. musket.

In the heart of Rhenish Prussia in the city of Wesel, Gustav Bloem was born on March 18, 1821. From an early age, Gustav had a knack for industry and mass production, working at a button factory in Lüdenscheid. It was here where he first fell in love with the world of machinery and developed an interest in explosives.

By 1848, Bloem had taken a daring step into the world of ammunition. With the help of his chemist friend Friedrich Nebe, he opened a small primer factory in Derendorf. However, Bloem’s dreams seemed to shatter just nine months later when an explosion leveled his factory. Despite this, he was far from giving up.

The world of firearms has a fascinating history, with many twists and turns. One such exciting era involves the early pistols made by Casimir Lefaucheux. Recent discoveries of some of his rare firearms have sparked curiosity about the relationship between Lefaucheux and another inventor, Béatus Béringer. In this article, we’ll take a look at the story behind these two inventors and the intriguing features of their early pistols.

Nathan Russell Davis, known as N.R. Davis, was a pioneer in the American firearm industry. Born in 1828, he established N.R. Davis & Sons, a company that would leave a lasting mark on the firearm manufacturing landscape. From its humble beginnings in a small shop in Assonet, Massachusetts, to its evolution into a respected firearm manufacturer, the company’s history is a testament to Davis’s vision and resilience. This article delves into the early years of N.R. Davis’s companies, highlighting their innovative contributions such as a unique pinfire shotgun, and the company’s enduring legacy.

Discover Our Digital Collection; Coming Soon at Lefaucheux.com

Welcome to The Lefaucheux Museum, a dedicated online space celebrating the extraordinary history and craftsmanship of the Lefaucheux family. Immerse yourself in a rich digital experience that showcases an extensive collection of Lefaucheux artifacts, including firearms, original documents, and personal memorabilia.

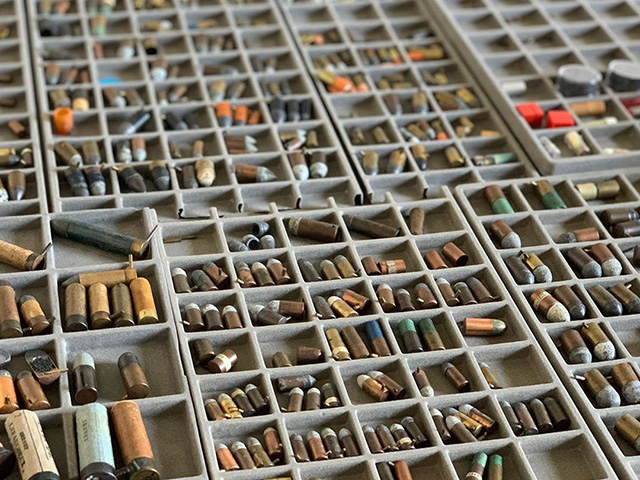

Hello, my name is Aaron Newcomer. I am a collector and researcher of early 19th century breech-loading firearms systems, with a particular focus on the work of Jean Samuel Pauly and Casimir Lefaucheux. I collect cartridges and documents related to these types of firearms and conduct research on these topics, furthering my understanding and knowledge of these historical firearms and their place in the evolution of firearms technology. My collection and research reflect my dedication to preserving and understanding the history and technical innovations of these early firearms systems.

Hello, my name is Aaron Newcomer. I am a collector and researcher of early 19th century breech-loading firearms systems, with a particular focus on the work of Jean Samuel Pauly and Casimir Lefaucheux. I collect cartridges and documents related to these types of firearms and conduct research on these topics, furthering my understanding and knowledge of these historical firearms and their place in the evolution of firearms technology. My collection and research reflect my dedication to preserving and understanding the history and technical innovations of these early firearms systems.